Reflection at the End of my Pilgrimage

Matsuri No Ato- A Reflection at the End of My Pilgrimage

I have been home for over a month now, having returned from Japan after completing the Shikoku 88 temple pilgrimage, and I am finding myself in a hero’s lull or a matsuri no ato moment.

This is a moment after completion of a meaningful project when energy drops, motivation thins, and what was meant to feel like arrival feels strangely flat. In Japanese culture, this moment has a name: matsuri no ato, literally “after the festival.” In the Hero’s journey, it’s called the Hero’s Lull that follows the quest. In psychology, it’s sometimes referred to as “completion depression”.

Have you ever encountered such a moment and feeling?

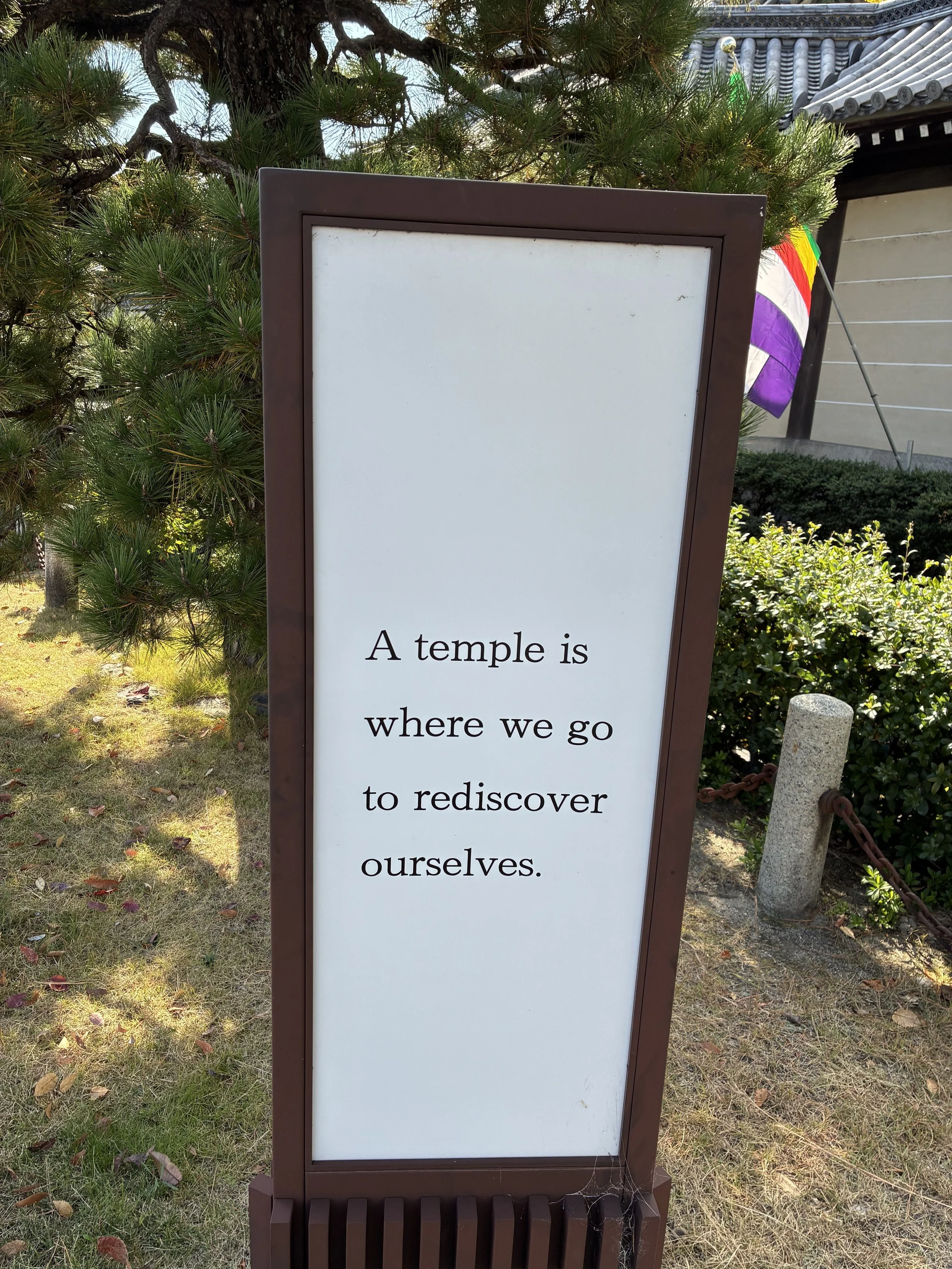

On November 12, I visited Temple 28 on the Shikoku 88 temple pilgrimage, completing the journey I had started in 2016. It took me four trips to the island of Shikoku (in 2016, 2023, 2024, and 2025) to visit all of the 88 temples, roughly twenty on each trip, visiting some more than once.

This matsuri no ato moment I am finding myself in, describes the quiet that settles once a festival ends, lanterns are taken down, crowds have dispersed, streets have returned to ordinary rhythm. The celebration was real and meaningful, and precisely because of that, its ending leaves a noticeable stillness behind. If you have attended any matsuri or festival in Japan, you can understand the profound meaning of the term.

However, matsuri no ato is not a problem to fix. It is a natural emotional phase: my nervous system is settling, my mind reorganizes after intensity, the identities I had left behind return, not quite fitting anymore. The emptiness or boredom is not evidence that something went wrong—it is actually evidence that something truly mattered. It’s a natural pause that deserves acknowledgement before the next rhythm of life begins.

Similarly, using the stages of the Hero’s journey, the Hero’s Lull comes when the quest is completed, the dragon is defeated, the treasure is secured. During the quest, purpose is supplied externally by danger, challenge, and necessity. Once that forward pull disappears, the nervous system downshifts, and the psyche must reorganize without the scaffolding of urgency and survival. The lull is a threshold for transformation, a time to reflect on who we have become in the course of the journey. Modern culture often skips this chapter of integration, rushing straight to the next goal.

As a coach, I know this, and yet, I have to work hard to resist jumping onto another goal or project, skipping over this integration phase. So I am taking my own medicine and reflecting.

Using the metaphor of matsuri no ato, here are the reflection prompts I am using to stay in this liminal phase a little longer:

What part of me was most alive during this “festival”—beyond outcomes or tasks?

What am I missing now: the goal itself, the structure it provided, or the version of myself it called forth?

If this quiet could speak, what would it name?

The festival does not end so that something better can begin—it ends so that something different can take shape. The next direction will emerge naturally, once the stillness has been honored.

That is what the coach in me says: Pause. Breathe. Acknowledge.

Once the feeling has been acknowledged, the bridge is not “What’s the next goal?” but “What wants continuity?” and “What doesn’t?”.

Let me know how this lands with you and if you have ever been in a hero’s lull.

Nichinichi-kore-kojitsu- at Moss Temple plus Fall Colors, Kyoto

Nichinichi-Kore-Kojitsu or Every Day is a Wonderful Day.

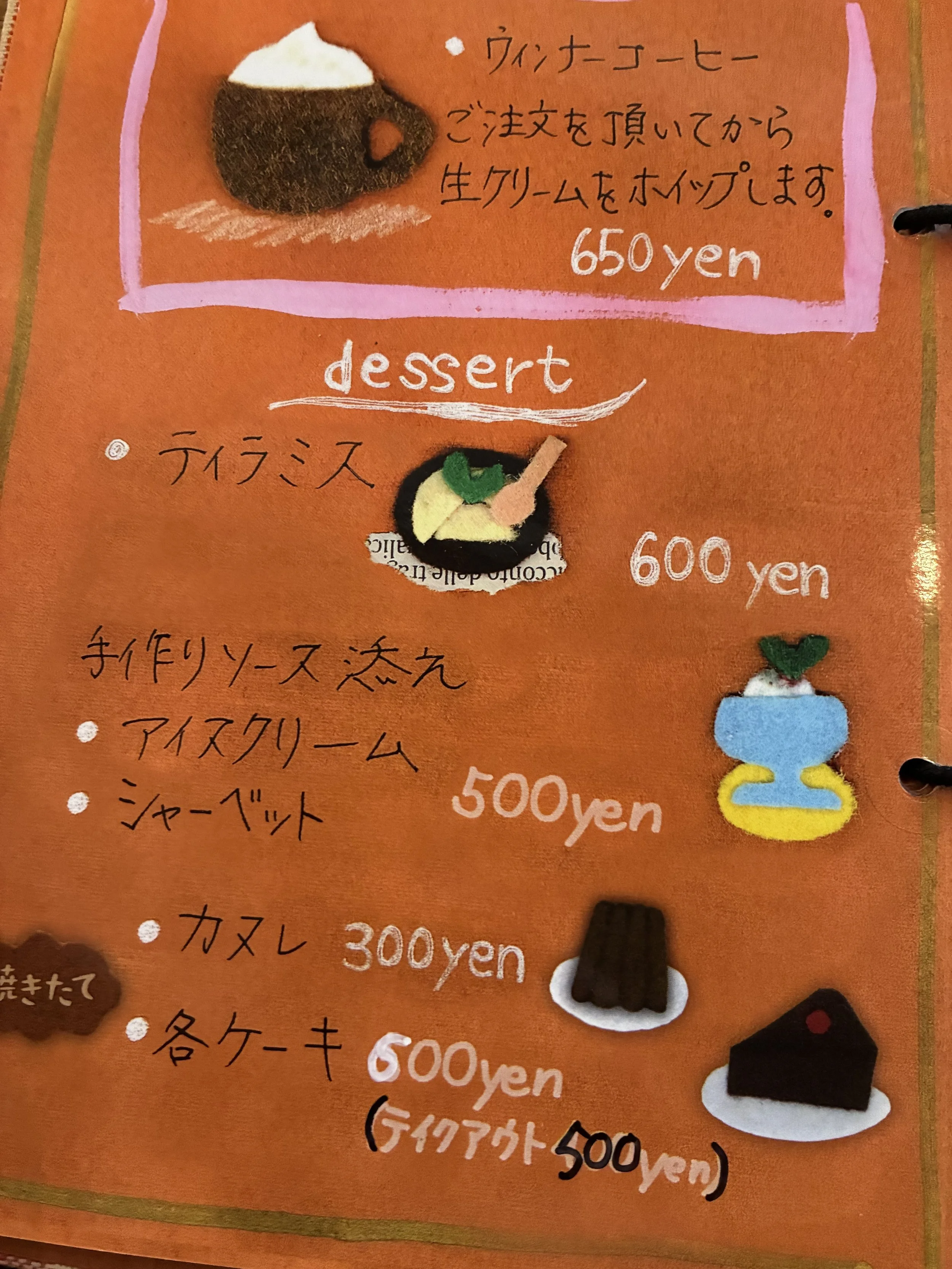

As I visit Saihoji Temple -also called Moss Temple, a Zen temple at the foot of the mountains West of Kyoto, and sit down for my lunch in the rest hut that is provided to that effect, I read their article “Zen Words for Everyday Life”.

The first sentence reads:

Life is not about what is“good” or “bad”. What is important is to consider how to make each day enjoyable.

According to Zen practice and as told in a famous koan from the Blue Cliff Record, life is not about what is“good” or “bad”. What is important is to consider how to make each day enjoyable.

SKY ABOVE

Earth Below

Kizuki

Last of 88- Dainichiji Temple, Noichi

This is the last temple that I visited on the Shikoku 88 temple pilgrimage completing the journey I started in April 2016. That day I saw two other pilgrims. It was very quiet, almost too quiet.

This temple (#28), as many others on the pilgrimage, is dedicated to Dainichi Nyorai which I have encountered many times on my journey. It’s also named after the deity. Dainichi Nyorai is considered to be the greatest Nyorai, one of the thirteen enlightened beings or deities that are represented in Shingon buddhism.

(Inside the main hall of each temple site, there is a statue of the deity which is considered to be the central religious figure of each site).

One specific encounter with Dainichi Nyorai for me happened at a special ceremony on Mount Koya in early October called Kechien Kanjo: Kechien means "to form a connection" and Kanjo means "anointment" or "initiation."

This ceremony is usually reserved for monks during advanced training, but at Mount Koya, anyone can participate. During the ceremony, participants are blindfolded and guided in front of a mandala, which is a symbolic map of the Buddhist universe. They are asked to throw a flower onto the mandala. The spot where the flower lands shows which Buddha they are now spiritually connected with. My flower landed on Dainichi Nyorai.

During the two-hour ritual, together with hundreds of other blind folded pilgrims, I was guided into the Kondo Hall as we recited repeatedly “Namu Daishi Henjo Kongo”, the mantra of Kobi Daishi, the saint who founded Shigon buddhism in Japan and the 88 temple pilgrimage in the eight century. We also chanted the Dainichi Nyorai’s mantra: “Om, Abira unken, bazara dadoban”.

The point of the Kechien Kanjo ceremony is to lead you to realize that you are the Dainichi Nyorai yourself.

There was a shop at the bottom of Temple 28. To keep the connection alive and to return with a memento of that day, I bought a bracelet with a pearl through which a picture of Dainichi Nyorai can be seen. I shared my accomplishment with the woman at the store. She congratulated me. I thanked her for celebrating me and I left.

SKY ABOVE

EARTH BELOW

kizukis

More Beauty: Cosmos, Goma and Herons

Poem of the One World by Mary Oliver

Heron at Flea Market- To-ji Temple, Kyoto

Herons are everywhere in Japan, wading on the banks of the Kamogawa river in Kyoto, fishing in a canal by the To-ji temple while tourists and shoppers walk by to visit the monthly flea market, or perched on a tree or house in a village.

I have been wondering what the sightings of so many of these majestic birds mean. A search on the internet results as follows:

“Seeing a blue heron can be interpreted as a symbol of patience, self-reliance, and good fortune, suggesting a message to pause and act with grace. It can also represent a spiritual messenger, symbolizing divine communication, inner wisdom, or a reminder to be still and self-determined.”

SKY ABOVE

EARTH BELOW

Fire Purification Ritual- Tanukidani-san Fudo-in Temple, Kyoto

Aki Matsuri Fall festival at Tanukidani-san Fudo-in Temple in Kyoto

In Japan, the changing of the seasons is celebrated with rituals, usually those that focus on praying to cleanse oneself of past wrongs and to pray for blessings in the future. Tanukidani-san Fudo-in Temple celebrates its Fall Festival called Aki Matsuri in early November. The Aki Matsuri involves visitors writing their wishes on wooden tablets (gomagi) and monks who practice a form of mountain asceticism called Shugendo throwing those wooden tablets into a sacred bonfire (goma) as witnessed in the videos. With the sound of Buddhist sutras in the air, the wishes of the participants are blessed as they are engulfed in the fire. I heard about Shugendo, a blending of Shinto and Buddhist practices, from Alena, the mountain guide that I worked with on my Women’s Pilgrimages. This blending of Shintoism and Buddhism is particularly evident at Tanukidani-san Fudo-in temple. Just the name of the temple reflects that: Tanuki is the name for the Japanese raccoon dog and is deeply embedded in the Shinto folklore while Fudo Myyo is an important deity in Shingon buddhism as a wrathful protector of the Buddhist law. To get to the temple, you have to walk 250 steps. On most of the steps a small statue of a tanuki has been placed. The main temple enshrines a statue of Fudo Myyo in a cave. There is a waterfall for the practice of Takigyo, an ancient ascetic ritual where practitioners stand under freezing, pounding waterfalls to purify body and mind, achieving spiritual clarity and connection with nature by enduring intense sensory shock, chanting mantras, and confronting internal challenges, leading to feelings of rebirth and mental reset. It's a core part of Shugendo. Alena has written extensively about Shugendo and how as a young woman from Eastern Germany, she came to become a practitioner. You can find her writings in a set of articles titled Shugendo Diaries. Attending Aki Matsuri at this temple was the third time I visited the grounds. During the previous two visits, I had been mostly on my own or with a couple of other visitors. The fire festival made the place and Shugendo come to life in a spectacular way and allowed me to further appreciate the integration of the two traditions. Enjoy my amateur videos!

SKY ABOVE

Earth below

kizuki: tanukis or raccoon dogs statues

To read mor about tanukis, check out my May 2025 newsletter then watch the studio Ghibli movie Pom Poko.

In January, after the devastating fires in Los Angeles, I wrote about Fudo Myoo and how to use the strong and fierce energy of anger in beneficial, protective, ways.