A 20 minute New Beginnings and Habit Change Meditation from the Mindful Movement

Start Close In by David Whyte

Self-Reflection for the End of Year

On The Wisdom of Walking in the Woods

“When the eyes and the ears are open, even the leaves on the trees teach like pages from the scriptures”

If you have visited my website, you may have been intrigued by my Medicine Walk offering called (Inner Compass) Wisdom Walk. Or, if you are a client, I may have suggested that you take on a walk as a new practice for your coaching program: labyrinth, hike or meditation walks are some of the practices I recommend often. But why? I strongly believe in the benefits of walking in nature to reconnect with oneself and the world. In this newsletter, I want to share some texts that point to the same conclusion.

Much has been written over the years about the physical, emotional and spiritual benefits of walking in nature (Thoreau: “An early morning walk is a blessing for the whole day.”, Muir: "In every walk with nature one receives far more than he seeks.", Rousseau: “I can only meditate when I am walking. When I stop, I cease to think, my mind only works with my legs.”), but in recent times, nobody has written more beautifully and more completely on the subject than Rebecca Solnit in her 2000 masterpiece Wanderlust: A History of Walking.

She writes: “Walking, ideally, is a state in which the mind, the body, and the world are aligned, as though they were three characters finally in conversation together, three notes suddenly making a chord. Walking allows us to be in our bodies and in the world without being made busy by them. It leaves us free to think without being wholly lost in our thoughts.[…]

Walking itself is the intentional act closest to the unwilled rhythms of the body, to breathing and the beating of the heart. It strikes a delicate balance between working and idling, being and doing. It is a bodily labor that produces nothing but thoughts, experiences, arrivals.[…]

The rhythm of walking generates a kind of rhythm of thinking, and the passage through a landscape echoes or stimulates the passage through a series of thoughts. This creates an odd consonance between internal and external passage, one that suggests that the mind is also a landscape of sorts and that walking is one way to traverse it. A new thought often seems like a feature of the landscape that was there all along ..“

When you go on a Medicine walk, this is exactly what happens. Your mind, heart and body are in a conversation with the world. Your body relaxes, your mind slows down, your heart opens. You suddenly hear a message that you had missed before. Your attention is drawn by a natural element and you inquire: “what is this?”, “why am I receiving this now?”. As Kabir, a 15th-century Indian mystic poet and saint, says: When the eyes and the ears are open, even the leaves on the trees teach like pages from the scriptures.

Further proof of the benefits of being in nature with or without walking, can be found in the book The Nature Fix by Florence Williams. The Nature Fix demonstrates that our connection to nature is much more important to our cognition than we think and that even small amounts of exposure (just 5 hours per month according to the author) to the living world can improve our creativity and enhance our mood. Earlier in the year I wrote about Shinrin-Yoku or Forest Bathing and I was excited to read about it again in this book The Nature Fix- Why Nature Makes Us Happier, Healthier and more Creative by Florence Williams. Written in a journalistic style with tons of supporting evidence, scientific data, anecdotes and well told stories, Williams explores different beneficial aspects of Nature and takes us on world tour starting with Japan, then Korea, Finland and Scotland. She also takes us on a tour of our senses: starting with our sense of smell (aromatherapy in Japanese cypress forests), our sense of hearing (bird songs in Korea) and our sense of sight (fractals in Finland). Her book brings a global perspective on the status of the latest studies of nature practices and their alleged benefits. She affirms that 5 hours a month immersed in nature is enough to make a difference to our well-being. The best summary of the book is given in this YouTube video created by the author.

So remember: “Go outside. Go often. Bring friends. Breathe”.

An Apple Tree Was Concerned- A Poem by Hafez

An apple tree was concerned

about a late frost and losing its gifts

that would help feed a poor family close by.

Can't the clouds be generous with what falls from them?

Can't the sun ration itself with precision?

They can speak, trees,

they can say the sweetest things

but it takes special ears to hear them,

ears that have listened to people

with great care.

The Power of Reframing

In film, reframing is a change in camera angle without a cut and often changes a scene’s focus. Bill Burnett and Dave Evans from the d.school at Stanford University mention reframing as one of the five principles of Design Thinking that is useful when applied not just to product design but also to the process of designing one’s life. In their best-selling book, Designing Your Life, How to Build a Well-lived, Joyful Life, they define reframing as follows: “Reframing is how designers get unstuck. Reframing also makes sure that we are working on the right problem. Life design involves key reframes that allow you to step back, examine your biases, and open up new solution spaces”.

A Blessing For the New Year- Beannacht by John O'Donohue

Feeling stuck? Should you turn to therapy, coaching or consulting? An infographic from the International Coaching Federation.

The Sycamore by Wendell Berry

In the place that is my own place, whose earth

I am shaped in and must bear, there is an old tree growing,

a great sycamore that is a wondrous healer of itself.

Fences have been tied to it, nails driven into it,

hacks and whittles cut in it, the lightning has burned it.

There is no year it has flourished in

that has not harmed it. There is a hollow in it

that is its death, though its living brims whitely

at the lip of the darkness and flows outward.

Over all its scars has come the seamless white

of the bark. It bears the gnarls of its history

healed over. It has risen to a strange perfection

in the warp and bending of its long growth.

It has gathered all accidents into its purpose.

It has become the intention and radiance of its dark fate.

It is a fact, sublime, mystical and unassailable.

In all the country there is no other like it.

I recognize in it a principle, an indwelling

the same as itself, and greater, that I would be ruled by.

I see that it stands in its place and feeds upon it,

and is fed upon, and is native, and maker.

Photo by David Whyte

Who is Challenging Your Worldview?

Gary Larson- The Far Side

Is Anybody Challenging Your Worldview?

Every one of us needs a team member, a partner, a friend or a coach to let us know about the large insect that is obstructing our view of the world.

Partnering with a coach could be beneficial for you!

"Your Are Living In A Poem" and two more Japanese concepts that I love: Yutori and Shisa Kanko

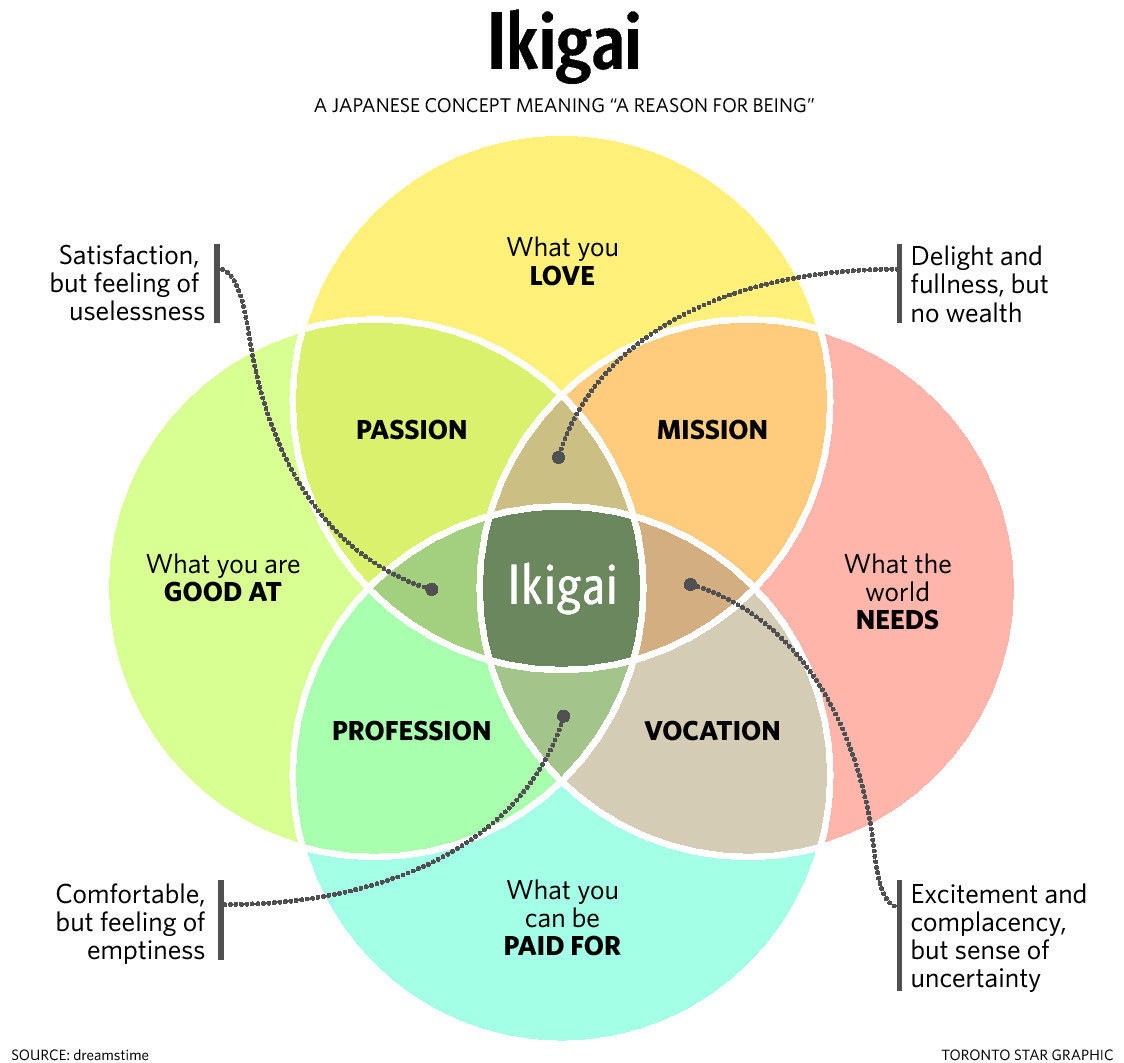

In my last two posts, I have written about Shirin-Yoku or Forest Bathing and Ikigai or Raison d'Être. Today I want to tell you about two more Japanese terms or concepts that I love: Yutori and Shisa Kanko.

Yutori is a term that I first heard mentioned by Naomi Shihab Nye in an interview with Krista Tippett on her OnBeing radio podcast. In the interview, Naomi Shihab Nye, an American poet, tells the story of a class she was teaching in Japan:

I just came back from Japan a month ago, and in every classroom, I would just write on the board, “You are living in a poem.” And then I would write other things just relating to whatever we were doing in that class. But I found the students very intrigued by discussing that. “What do you mean, we’re living in a poem?” Or, “When? All the time, or just when someone talks about poetry?” And I’d say, “No, when you think, when you’re in a very quiet place, when you’re remembering, when you’re savoring an image, when you’re allowing your mind calmly to leap from one thought to another, that’s a poem. That’s what a poem does.” And they liked that.

And a girl, in fact, wrote me a note in Yokohama on the day that I was leaving her school that has come to be the most significant note any student has written me in years. She said, “Well, here in Japan, we have a concept called ‘Yutori.’ And it is spaciousness. It’s a kind of living with spaciousness. For example, it’s leaving early enough to get somewhere so that you know you’re going to arrive early, so when you get there, you have time to look around." And then she gave all these different definitions of what Yutori was to her.

But one of them was — "and after you read a poem just knowing you can hold it, you can be in that space of the poem. And it can hold you in its space. And you don’t have to explain it. You don’t have to paraphrase it. You just hold it, and it allows you to see differently." And I just love that. I mean, I think that’s what I’ve been trying to say all these years.

So how does this relate to coaching you might ask? Well, coaching is an act of self-discovery and it all starts by giving yourself space and time for inner work. There are a number of practices that people engage in which add Yutori/spaciousness to their life: some people have a meditation practice, others embrace mindfulness in whatever they do, others include more silence and solitude in their lives by starting their meals in silence, or taking a silent sensory walk in the woods every day. Others journal or declutter their personal space or just spend half an hour gazing in a square foot of their garden. It's whatever brings you space and time to wonder. I personally like to start my day by reading a poem and this is why the story from Naomi Shihab Nye resonates with me. So let me share with you this poem by Rumi that gave me Yutori this morning:

Watch the dust grains moving

in the light near the window.

Their dance is our dance.

We rarely hear the inward music,

but we are all dancing to it nevertheless,

directed by the one who teaches us,

the pure joy of the sun,

our music master.

The second Japanese term I want to introduce is Shisa Kanko translated to English as "pointing, calling, and acting". It's a kind of checklist, bringing consciousness and mindfulness to whatever you are doing, specifically when engaged in repetitive tasks. In Japan, Shisa Kanko was first used by train operators and is now widespread in industrial settings. A 1994 study by Japan Railways showed a reduction of 85% of mistakes made by conductors when using Shisa Kanko. If you travel to Japan, you will notice this pointing and calling. I find it fascinating. So again, how is this relevant to coaching, you may ask? Well, as mentioned above, coaching is an act of self-discovery. Practicing Shisa Kanko with your own behaviors, emotions, or beliefs is a good way to start noticing the habits of the mind and to bring awareness to the situation at hand. Until you notice (point) and name (call) the behavior you want to change, it's impossible to change it (act). (More about Shisa Kanko in Japan in this article by Alice Gardener.)

Do you practice Shisa Kanko in your life? Maybe you use the technique when meditating? When you label your thoughts and emotions as part of your sitting practice, you are doing a form of Shisa Kanko. When a thought or emotion arises, you notice it (point), label it (call), and let it go (act), returning to the breath or to whatever focal point you were using for your meditation. I find I am using the technique with my teenager who is learning to drive when I ask him to point, call, and act at a stop sign, a red light, a pedestrian crossing, or a freeway entrance.

So I will leave you with two questions today:

- Where do you find your Yutori?

- How do you practice Shisa Kanko in your life?

Warmly,

Anne-Marie

Have you found your Ikigai?

Ikigai is a Japanese term that combines the characters for "life" and "worthwhile". The best translations would be "raison d' être" in French or "life purpose" in English. Your Ikigai is this place where you are able to combine what you love, what you are good at, what you can be paid for and what the world needs.